Clone Wars: Using Discomfort to Define Humanity in Science Fiction

The classic internet dilemma: would you fuck a clone of yourself?

While some people say they would “totally fuck their clone because [they] want to know if [they’re] good in bed,” and others would “not have sex with [their] clone because what if [their] clone is evil,” the presence of clones in dystopic and science fiction literature prevails beyond the scope of an absurd Buzzfeed quiz (Broderick et. al). Kazuo Ishiguro's novel Never Let Me Go and Kogonada's film After Yang work to humanize clones whereas David S. Goyer's television adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series depicts clones as personifications of unchecked power. Although ideas of free will and the debate of nature versus nurture have persisted for centuries and likely will continue to for years to come, the use of clones in science fiction creates an opportunity to consider these questions and explore definitions of humanity through use of the clones’ unique ability to make the people around them—both in the contexts of their stories and for the audience observing them—extremely uncomfortable. This discomfort, often referred to as an uncanny valley, exists only within the context of humanoid forms, allowing clones to be the perfect medium through which to explore the inherent feelings of disturbance surrounding them.

Uncanny Valley, in graph form

Never Let Me Go’s Kathy is, as far as the reader knows, an individual. After Yang’s Ada is a clone physically but is portrayed as having as much free will as traditional people. Foundation’s Brothers Dawn and Day are technically not true clones of Cleon I, despite appearances. Yet in all of these fictional worlds, the societies these characters inhabit refuse to wholly accept them, ultimately tying back to the feelings of discomfort surrounding their very existence. Kate Cantrell and Lesley Hawks explain this discomfort, saying that “a robot that speaks with a human voice rather than a synthetic one may create a visual-auditory mismatch that provokes uncertainty as to whether the robot is human or artificial. (...) an uncanny sensation—a feeling of uncertainty or discomfort—emerges from the observer’s doubt regarding what category the entity belongs to, or what the entity is” (Cantrell et. al 13). This feeling of uncertainty, categorized under the term “uncanny valley,” is the core reason for the mistreatment of clones in the stories they occupy, and exactly why those stories’ redefinitions of humanity in relation to the clones is so profoundly unique.

Definitions of humanity widen and narrow in society’s narrative, depending on who is in control and what they want to say; morally objectionable people in real life are often put into one box (human) or another (inhuman) depending on how comfortable the storyteller is with their own humanity. Steven Keslowitz elaborates on this idea, saying that “it is an unfortunate human tendency to define other groups and individuals by reference to one’s self” (Keslowitz 81). Keslowitz argues that humans inherently view the world and the people around them in relation to how they view themselves, so if people see clones, beings they do not consider to be like themselves, they must automatically consider the clones something other than human. Therefore, in order to make arguments about the humanity (or lack thereof) of clones, the stories in question must redefine humanity itself.

If a person is created as genetically identical to someone else, are they an individual? If this person, this clone, is created for an explicit purpose, will they fulfill that purpose because they are programmed to do so or because they are taught to? Antony Mullen argues that "the clones of Never Let Me Go are seen to perform an identity of their choosing – but the circumstances of their birth undermine any element of choice in deciding their future" (Mullen 12). In essence, the clones in Ishiguro's novel are able, for the most part, to determine individual actions and form an identity (such as what books to read or who to be friends with) but only within the confines of the society that they are raised in. One could argue that she has free will, that she is a product of her environment, but only on a small scale; every supposedly individual choice she makes is overshadowed by the looming presence of the donations. This contradiction might exist in some form in stories about traditional humans, but these humans still ultimately have choices that the clones in the aforementioned narratives do not. (Harry Potter, for example, might be prophesied to face Voldemort, but a series of choices from various individuals are what leads him to the final battle). Free will is something that people generally believe they have, so the fact that the clones are not afforded the same privilege effectively alienates them, meaning their humanity needs to be proven in other ways.

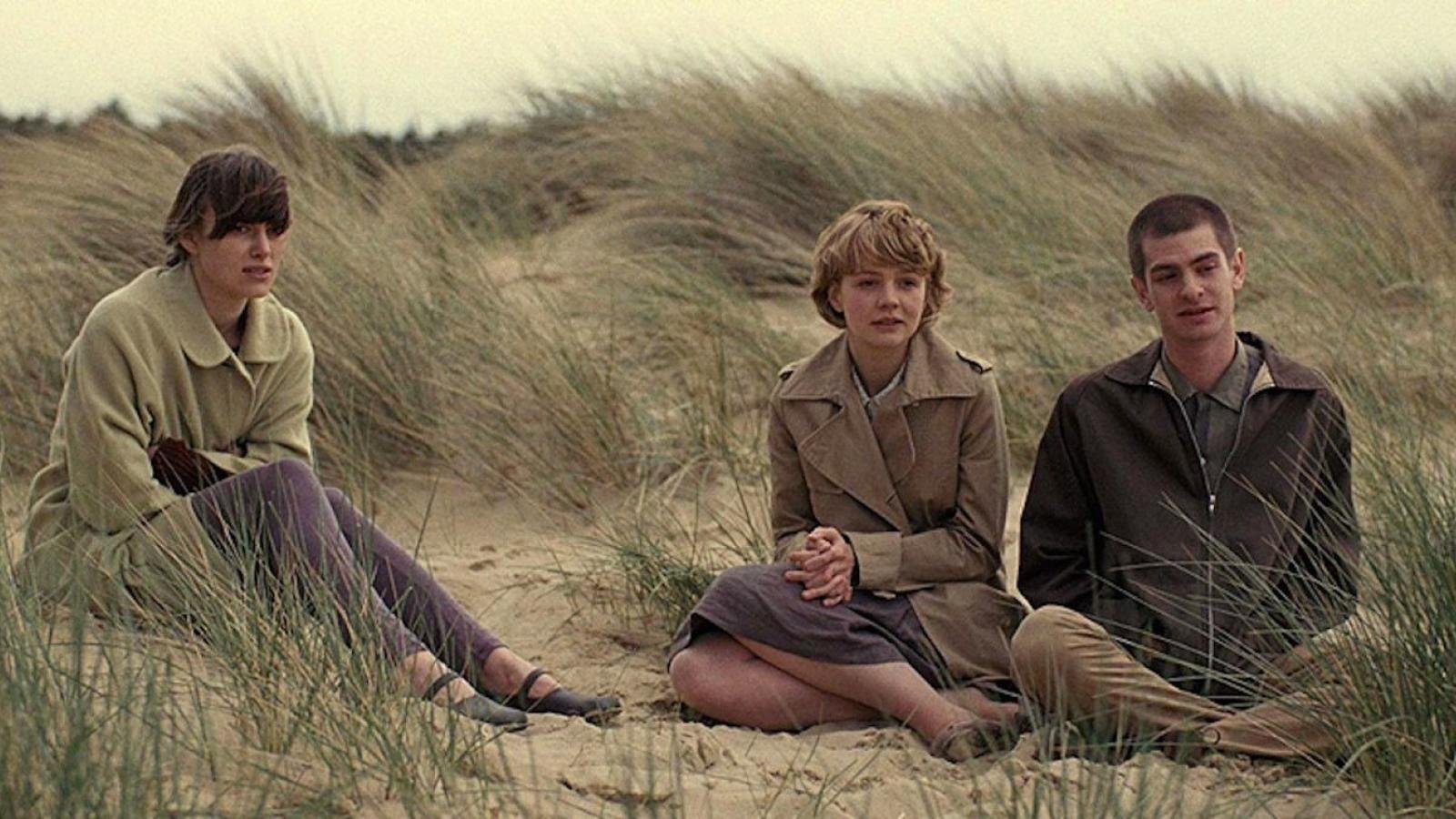

Never Let Me Go, 2010 film dir. Mark Romanek

From the very first lines of Never Let Me Go (“My name is Kathy H. I’m thirty-one years old, and I’ve been a carer now for over eleven years”), the reader is entrenched in the mind and perspective of Kathy, the protagonist, making them immediately sympathetic towards her, and therefore humanizing the idea of clones when it is later revealed that she is one (Ishiguro 3). Kathy’s perspective is essential to the reader’s understanding of her world, to the point that even when the realization about her and her peers’ genetics is revealed, it still comes secondary to her journey as a carer and her relationships with Ruth and Tommy. By following Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy from their childhoods at Hailsham to their adolescences at the Cottages to their eventual fates as donors and carer alike, the reader is given an inside look at the characters’ growth and development; despite their circumstances hugely differing from those in the real world, their experiences are so universal (first crushes, curiosity, jealousy, lying about having read books) that they become indistinguishable from a traditional definition of a human being, and indistinguishable from the readers themselves. Additionally, by immersing the reader so strongly in Kathy’s mind and perspective, and by choosing to forego depicting the outside world’s perspective, Ishiguro creates a context through which the reader can view Kathy and her friends as peers rather than creatures to be observed under a microscope.

After Yang malfunctions in After Yang, Jake sets out to fix him, and when it appears that he cannot, he seeks out the person who knows Yang better than anyone else: Ada, a clone. While the plot of After Yang centers around Yang himself, Ada has more time on screen in the present than he does; Jake’s acceptance of his own grief over Yang’s death allows him to acknowledge Ada’s individuality and humanity, and as this change progresses throughout the film, Ada’s presence effectively becomes more solidly and traditionally human. In the context of the film, Ada is created as a solution to the sadness that Yang and his previous owner feel due to the loss of a loved one, but by exploring the relationship that she and Yang build, completely separate to her origin, she is shown as an individual in her own right, and therefore humanized. Although Ada is established as an individual person in After Yang, ideas about individual experience in opposition to society’s stance on cloning become much more blurry when compared to Never Let Me Go and Foundation. In all three works, clones are viewed negatively by at least one party (most of society in Never Let Me Go, Jake in After Yang, and the entire universe in Foundation), but where the first two works show ways in which clones are indistinguishable from natural-born humans, the third initially depicts clones as antagonists, unable to escape their own fate and decidedly colder than the people surrounding them—only to later subvert itself.

Tommy’s art, Never Let Me Go film adaptation

Questioning and redefining humanity forces thinkers to ask what parameters they use to define humanity. If the clone has free will, are the just as human as you or me? If they don’t have free will but this is a result of the structures of their society, what then? What makes you human? Your interests? Your attitudes? Your relationships to others, your beliefs, your potential for growth? If you live in the worlds of Never Let Me Go or Foundation, you define humanity through something immaterial: souls. Souls are an intangible but essential belief in Never Let Me Go, and the idea that natural-born humans have them but clones do not is the society’s core argument against the equal treatment of clones. The “gallery,” as students of Hailsham call it, is therefore essential to the Hailsham caretakers’ quest to prove the humanity of the clones. Souls cannot be literally seen in Never Let Me Go, but the people in Ishiguro’s alternate-universe Britain are willing to view art as a window into the soul. Mullen argues that the existence of the gallery has double-meaning, saying that “to allow the clones to develop a narrative self and express themselves through possessions and creativity was not just a noble lie, but an experiment intended to challenge societal perceptions of what ‘human’ means. (...) the humanities are not presented as complicit with the political system at work in the novel – but a means by which it could be resisted and a way of caring” (Mullen 10). Mullen adds to the souls narrative by making a case for the perpetuation of the rift between the humanities and the sciences within Never Let Me Go. He explains that while the Hailsham students’ art might seem antithetical to the cruel scientific presence of the donations, the existence of humanities, and the existence of the belief in souls, serves as an act of rebellion against the system itself, perhaps just as Miss Emily and Madam intend.

Foundation episode 8, “The Missing Piece”

In contrast to this subjective interpretation of souls is the more literal one in Foundation. The question of souls in this universe is spiritual, with humans setting out to complete a harrowing, life-threatening journey through the desert to seek enlightenment, an achievement only ultimately possible if the traveler has a soul. Brother Day embarks on this journey to prove to himself and others that he, unlike what is said about him due to his status as a clone, has a soul. This journey ends in disappointment, but also poses a question: how human is human enough? The major reveal of the season finale is that both Brothers Dawn and Day are not true clones of Cleon I — both of their genetic materials were altered before their births, such that they physically appear to be perfect copies as they should be, but mentally are different. If even Brother Day, someone who is not a perfect clone, does not have a soul, then how much of him has to be changed in order for him to be considered human? Dawn and Day exist as exceptions to the rules of the society their predecessors created; they are both not clone enough for Demerzel (their humanoid assistant) and Brother Dusk, but not human enough for the rest of society to accept.

Ultimately, because Never Let Me Go, After Yang, and Foundation all humanize (and sometimes dehumanize) clones in various ways while also acknowledging the fact that their existence makes the people around them uncomfortable, all three narratives effectively pose a debate to the reader or viewer, asking them to consider the boundaries and intricacies of their own definition of humanity. By forcing the audience to simultaneously empathize with clones and sit in their own discomfort about the clones’ existence, storytellers like Ishiguro, Kogonada, and Goyer expand the idea of what it means to be human, and whether being human is even the ideal form of existence. In After Yang, Jake asks Ada whether Yang wished he was human, to which she replies, “that's such a human thing to ask, isn't it? We always assume that other beings would want to be human. What's so great about being human?” (Kogonada). The questions Ada poses to Jake cause him to reorient himself and his previously-held beliefs, and pushes the audience to do the same. In all of the narratives, the clones’ lack of free will paired with their relatable sensibilities causes the audience to question their own perceived free will. The clones’ search for self identity within the confines of their own world reflects the all-too-human quest for the same thing, especially in the 21st century. The clones’ existence is multifaceted, both scientifically inhuman and sociologically perfectly human. Once the readers and viewers come to understand and often even relate to the clones, they leave the narrative thinking about individuality, free will, and ultimately, whether the nature of their conception is what defines them as human or if the experiences they go through in life are more important.

Buzzfeed’s clone-copulation survey is all in good fun, but it truthfully reflects the questions posed in many clone narratives, especially the aforementioned three. Some people are unable to see the clones as individuals (“it'd be like having sex with your twin. Wrong and bad!”) while others go full speed ahead with the idea (“not only would I have sex with my clone, I'd probably make a bunch of clones and just get it on with all of them at once because that's how pro-clone fucking I am”) and are willing to integrate the clones as equals into their lives and societies (Broderick et. al). Where Never Let Me Go poses nuanced and empathy-based questions about clones, After Yang presents the uncanny valley effect in full force while questioning the importance of humans, and Foundation redefines and re-evaluates humanity itself, Katie Notopoulos and Ryan Broderick manage to present the same ideas with a simple question:

Would you fuck a clone of yourself?

Works Cited:

Broderick, Ryan and Notopoulos, Katie. “Can We Ask You A Really Weird Question?”

Buzzfeed News, 2015. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/iexplorer/hey-we-have-a-weird-question-for-you

Cantrell, Kate and Hawkes, Lesley. “Empathy, Anthropomorphism, and the Uncanny

Valley Effect: Why Audiences Strayed Away from the Film Adaptation of Cats.” 2021. The Journal of Pop Culture, 54: 571-593. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpcu.13021

Goyer, David S. Foundation, Apple TV+, 2021.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. Never Let Me Go. Faber and Faber, 2005.

Keslowitz, Steven. The Digital Dystopias of Black Mirror and Electric Dreams. McFarland

& Company, 2020.

Kogonada. After Yang. A24, 2022.

Mullen, Antony. “‘Kazuo Ishiguro and the Legacy of Aspirational Individualism’.” 2019.

C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 7(1): 2, pp. 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/c21.556